Hans-Bernd Zöllner

Translation by Nyein Chan May

English version of the article

၁။ မိတ်ဆက်

သခင်စိုးသည် ဒို့ဗမာ အစည်းအရုံးနှင့်၊ (၁၉၃၀) ပြည့်လွန်နှစ်များမှ (၁၉၄၈) ခုနှစ် နိုင်ငံလွတ်လပ်ရေးမရခင်အထိ မြန်မာ့လွတ်လပ်ရေးအတွက် တိုက်ပွဲ၀င်ခဲ့သည့် ဖဆပလ အဖွဲ့ချုပ်ကြီးတို့တွင် လွှမ်းမိုးမှုအရှိဆုံးအဖွဲ့၀င်များအနက် တစ်ဦးဖြစ်သည်။ သခင်စိုးသည် ဦးအောင်ဆန်းနှင့် ဦးနုတို့ကဲ့သို့ တက္ကသိုလ် မတက်ခဲ့ချေ။ သို့ရာတွင် နိုင်ငံရေးထဲသို့ မ၀င်ရောက်မီ ကုမ္ပဏီတစ်ခုတွင် အလုပ်လုပ်ကိုင်ခဲ့သည်။ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်အတွေးအခေါ်များကို အလွန်စွဲလန်းနှစ်ခြိုက်ခဲ့သည်ဖြစ်ရာ၊ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်စနစ်၊ ကွန်မြူနစ်စနစ်တို့ကို ပိုမိုများပြားကျယ်ပြန့်သည့် လူထုပရိသတ်ထံ မိတ်ဆက်ပေးသည့် စာအုပ်များ၊ ဆောင်းပါးများကို မြန်မာဘာသာဖြင့် ရေးသားခဲ့သည်။ နောက်ပိုင်းတွင်မူ အစိုးရကို ဆန့်ကျင်သည့် လက်နက်ကိုင်တော်လှန်ရေးတစ်ရပ်ကို အစပြုခဲ့သည့်၊ သေးငယ်သည့် ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ၏ ခေါင်းဆောင်သူ ဖြစ်လာခဲ့သည်။ (၁၉၈၈) ခုနှစ်နောက်ပိုင်း မြန်မာနိုင်ငံအကြောင်း ပညာရပ်ဆိုင်ရာနှင့် လူထုစိတ်၀င်စားမှုအပြောင်းအလဲကြောင့် သခင်စိုး၏ အရောင်စုံလင်လှသည့် ဘ၀နှင့် စရိုက်တို့မှာ လျစ်လျှူရှုခံလိုက်ရသည်။ သို့သော်လည်း သခင်စိုး၏ ဘ၀နှင့် စရိုက်တို့မှာ မြန်မာ့နိုင်ငံရေး၏ အဓိကအကြောင်းအရာများအပေါ် အလင်းပြလျက်ရှိသည်။

၂။ ကိုယ်ရေးအကျဥ်း

သခင်စိုးကို ယနေ့ မွန်ပြည်နယ်၊ ကျိုက္ခမီမြို့ (ဗြိတိသျှခေတ်က Amherst ဟု ခေါ်တွင်သည့်) အနီးရှိ၊ ကျောက်တန်းရွာ၌၊ (၁၉၀၅)(၁) ခုနှစ်တွင် မွေးဖွားခဲ့သည်။ (၁၉၂၂) ခုနှစ်မှ (၁၉၃၇) ခုနှစ်အထိ၊ Burmah Oil Company ၏ ဓာတ်ခွဲခန်းအကူအဖြစ် ရန်ကုန်မြို့အနီး၊ သန်လျင်မြို့ (ဗြိတိသျှခေတ်က Syriam ဟု ခေါ်) ရှိ လောင်စာဆီချက်စက်ရုံတွင် အလုပ်လုပ်ကိုင်ခဲ့သည်။ သူသည် စိတ်အားထက်သန်လှသည့် စာဖတ်သူတစ်ဦးဖြစ်ပြီး၊ ထိုစဥ်က မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတွင်းသို့ တရစပ်စိမ့်၀င်လျက်ရှိသည့် ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒအကြောင်းစာအုပ်များကို အထူးတလည် စိတ်၀င်တစားရှိလှသည်။

(၁၉၃၈)ခုနှစ် ဇွန်လတွင် သူရေးသားသည့် “ဆိုရှယ်လစ်၀ါဒ” စာအုပ်ကို နဂါးနီစာအုပ်အသင်းမှ ထုတ်၀ေသည်။ ယင်း နဂါးနီစာအုပ်အသင်းကို သခင်စိုးက သခင်သန်းထွန်း၊ သခင်နုတို့နှင့်အတူ တည်ထောင်ခဲ့ခြင်းဖြစ်သည်။ သခင်သန်းထွန်းက အဆိုပါစာအုပ်တွင် စကားချီးရေးပေးသည်။ သခင်စိုးအနေဖြင့် လောင်စာဆီကုမ္ပဏီတွင် အလုပ်မလုပ်တော့သည့်အခါ၊ သခင်နုက သူ့အား ရံဖန်ရံခါ ထောက်ပံ့ပေးသည်။ (၁၉၃၈)ခုနှစ်၊ သန်လျင်ရေနံမြေလုပ်သားများ သပိတ်တွင် အရေးပါသည့်နေရာမှ ပါ၀င်ခဲ့ပြီး၊ သခင် လှုပ်ရှားမှု၏ အဖွဲ့၀င်၊ ဒို့ဗမာ အစည်းအရုံး၏ ဗဟိုကော်မတီအဖွဲ့၀င်တစ်ဦး ဖြစ်လာခဲ့သည်။ အစည်းအရုံး၏ အသိဉာဏ်ပံ့ပိုးရာဌာနဖြစ်သည့် စာအုပ်အသင်းတွင် ဂုဏ်ထူးဆောင်အတွင်းရေးမှူးအဖြစ် ဆောင်ရွက်ခဲ့သည်။

(၁၉၃၉)ခုနှစ်၊ သြဂုတ်လတွင် သခင်စိုးသည် သခင်သန်းထွန်း၊ သခင်အောင်ဆန်းတို့နှင့်အတူ၊ လူအင်အား ၁၂ ဦး၊ ၁၃ ဦးခန့် ပါ၀င်သည့် ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီဗဟိုကော်မတီတစ်ရပ်ကို ဖွဲ့စည်းခဲ့သည်။ နောက်ပိုင်းတွင် ၄င်းကို ဗမာပြည်ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ၏ အခြေခံအုတ်မြစ်အဖြစ် မှတ်ယူကြသည်။ တစ်နှစ်အကြာတွင် သခင်စိုးသည် အခြားသော သခင်များကဲ့သို့ပင် ဗြိတိသျှတို့၏ ထောင်သွင်းအကျဥ်းချခြင်းကို ခံရသည်။ အကြောင်းမှာ ဥရောပတိုက်ရှိ ဖက်ဆစ်အင်အားစုများအား ဆန့်ကျင်တိုက်ထုတ်ရာတွင် မြန်မာက ဥရောပဘက်က ထောက်ခံအားပေးခဲ့ရာ၊ အပြန်အလှန်အားဖြင့် မြန်မာနိုင်ငံ၏ လွတ်လပ်ရေးကို ဗြိတိသျှတို့က ကတိပေးရန်ဖြစ်သည်။ ထိုသို့ ကတိပြုရန် ပျက်ကွက်သည့်အတွက် လှုပ်ရှားတောင်းဆိုမှုဖြစ်လာခဲ့သည်။ (၁၉၄၂)ခုနှစ် ဂျပန်တပ်များ ၀င်ရောက်လာချိန်၌ အကျဥ်းကျရာမှ လွတ်မြောက်ခဲ့ပြီး၊ သခင်အောင်ဆန်း၊ သခင်နု၊ သခင်သန်းထွန်းတို့နှင့်အတူ ဂျပန်တို့နှင့် မပူးပေါင်းဘဲ၊ ဧရာ၀တီဒေသမြစ်၀ကျွန်းပေါ်ဒေသတွင် ဂျပန်တို့ကို ဆန့်ကျင်သည့် မြေအောက်တော်လှန်ရေးလုပ်ဆောင်ရန် ထွက်သွားခဲ့သည်။ ထိုအချိန်က သခင်စိုးသည် သခင်သိန်းဖေမှ တဆင့် အိန္ဒိယနိုင်ငံရှိ ဗြိတိသျှအာဏာပိုင်များနှင့် အဆက်အသွယ်ရှိခဲ့သည်။ သခင်သိန်းဖေသည် မြန်မာနိုင်ငံမှ အိန္ဒိယနိုင်ငံသို့ ထွက်ခွာသွားသည့် ကွန်မြူနစ်ခေါင်းဆောင်တစ်ဦးဖြစ်သည်။ အခြားတစ်ဘက်တွင် ဂျပန်တို့က မြန်မာနိုင်ငံကို (၁၉၄၃)ခုနှစ်၊ သြဂုတ်လတွင် လွတ်လပ်ရေးပေးမည်ဟု အာမခံခဲ့သည့်အတွက်၊ အခြားသခင်များက ဂျပန်တို့ သတ်မှတ်ပုံစံချပေးသည့် မြန်မာအစိုးရထဲတွင် ၀င်ရောက်လုပ်ကိုင်ခဲ့ကြသည်။

(၁၉၄၃)ခုနှစ် ဒီဇင်ဘာလတွင် သခင်စိုးသည် ဗမာပြည်ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ၏ အထွေထွေအတွင်းရေးမှူးအဖြစ် ရွေးကောက်တင်မြှောက်ခံရသည်။ (၁၉၄၄)ခုနှစ် သြဂုတ်လတွင် ဖက်ဆစ်ဆန့်ကျင်ရေးအသင်း၊ နောက်ပိုင်းတွင် ဖက်ဆစ်ဆန့်ကျင်ရေးနှင့် ပြည်သူ့လွတ်မြောက်ရေးအဖွဲ့ချုပ် (ဖဆပလ) ဟု ခေါ်တွင်သည့် ဖက်ဆစ်ဆန့်ကျင်ရေးတပ်ဦး တစ်ရပ်ကို တည်ထောင်ရန်၊ မြန်မာ့တပ်မတော်၊ ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီနှင့် ဆိုရှယ်လစ်အင်အားစုများက သခင်စိုး၏ ဌာနချုပ်တွင် ဆွေးနွေးတိုင်ပင်ခဲ့ကြပြီး၊ မကြာမီအချိန်အတွင်းမှာပင် ရန်ကုန်မြို့၌ စနစ်တကျ အကောင်အထည်ဖော်ခဲ့သည်။ သခင်စိုးကို နိုင်ငံရေးခေါင်းဆောင်၊ သခင်အောင်ဆန်းက စစ်ခေါင်းဆောင်အဖြစ် အသိအမှတ်ပြုခဲ့ကြသည်။ ထို့နောက် သခင်စိုးက မြစ်၀ကျွန်းပေါ်ဒေသတွင် စစ်သားများ၏ နိုင်ငံရေးသဘောထားကို ကွပ်ကဲကြီးကြပ်ရသည့် နိုင်ငံရေးအကြံပေးတစ်ဦးဖြစ်သည့် နေ၀င်းနှင့် အတူတကွ ပူးပေါင်းဆောင်ရွက်ခဲ့သည်။

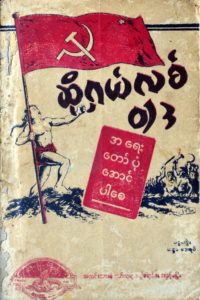

မတ်လတွင် အောင်ဆန်းဦးဆောင်သော ဖက်ဆစ်တော်လှန်ရေးဆင်နွှဲခဲ့သည့် မြန်မာ့တပ်မတော်၏ အကူအညီဖြင့်၊ မဟာမိတ်များ စစ်ပွဲကို အောင်နိုင်ပြီးသည့်၊ (၁၉၄၅)ခုနှစ် ဇွန်လတွင် ရန်ကုန်မြို့၌ အောင်ပွဲခံခဲ့သည်။ ထို့နောက် တစ်လအကြာတွင် သခင်စိုးအနေဖြင့် ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ အထွေထွေအတွင်းရေးမှူးနေရာကို လက်လွှတ်လိုက်ရသော်လည်း၊ ဗဟိုကော်မတီ၀င်တစ်ဦးအဖြစ် ဆက်ရှိနေဆဲပင်ဖြစ်သည်။ မိန်းမလိုက်စားခြင်းနှင့် အရက်သေစာသောက်စားမူးယစ်သည်ဟူသည့် စွပ်စွဲချက်တို့က သူ့ရာထူးကို လက်လွတ်ဆုံးရှုံးစေခဲ့သည်။ ဗြိတိသျှကွန်မြူနစ်တစ်ဦး၏ အကူအညီဖြင့် သခင်စိုးသည် တော်၀င်လေတပ်ပိုင်လေယာဥ်ကို စီးကာ၊ အိန္ဒိယနိုင်ငံသို့ သွားရောက်ပြီး၊ အိန္ဒိယကွန်မြူနစ်များနှင့် တွေ့ဆုံခဲ့သည်။ အိန္ဒိယမှ ပြန်ရောက်လာချိန်တွင် ဗြိတိသျှတို့နှင့် ပူးပေါင်းဆောင်ရွက်ခြင်းမှန်သမျှ မှားယွင်းကြောင်း၊ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံကို ဗြိတိသျှအုပ်ချုပ်ရေးအောက်မှ လွတ်မြောက်စေရန် လက်နက်ကိုင်တော်လှန်ရေးတစ်ရပ်ကို ဆင်နွှဲရမည်ဖြစ်ကြောင်း ပြင်းထန်စွာ ယုံကြည်ခဲ့သည်။(၂) ပါတီကို သူတစ်ဦးတည်း ဦးဆောင်ရန်ဆန္ဒနှင့် ပတ်သက်ပြီး၊ အချိန်ရှည်ကြာစွာ ငြင်းခုန်ဆွေးနွေးပြီးနောက်၊ သခင်စိုးသည် အခြားသော ဗဟိုကော်မတီ၀င် ခုနစ်ဦးနှင့်အတူ ဗမာပြည်ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီကို စွန့်ခွာခဲ့ပြီး၊ အလံနီကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီဟု အမည်တွင်သည့် ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ (ဗမာပြည်)ကို တည်ထောင်ခဲ့သည်။ သခင်သန်းထွန်း၏ ဦးဆောင်မှုအောက်မှာ အလံဖြူကွန်မြူနစ်များဖြစ်သည့်အတွက်၊ ပါတီအလံ၏ အဓိကအရောင်မှာ အနီရောင်ဖြစ်သည်။

သခင်စိုး၏ ပါတီသစ်ကို (၁၉၄၆) ဇူလိုင်လတွင် ဗြိတိသျှအစိုးရက မတရားအသင်းကြေညာပြီးနောက်၊ ပါတီမှာ မြေအောက်လှုပ်ရှားမှုအသွင် ပြောင်းသွားသည်။ သခင်စိုးက ဦးအောင်ဆန်း (၁၉၄၇ ဇူလိုင်လတွင် လုပ်ကြံခြင်းမခံရမီအချိန်အထိ အုပ်ချုပ်ခဲ့)၊ ဦးနု (၁၉၄၇ မှ ၁၉၅၈၊ ၁၉၆၀ မှ ၁၉၆၂ အထိ အုပ်ချုပ်ခဲ့)၊ နေ၀င်း (၁၉၅၈ မှ ၁၉၆၀၊ ၁၉၆၀ မှ ဆက်လက်အုပ်ချုပ်ခဲ့) တို့ ဦးဆောင်သည့် အစိုးရများကို (၁၉၇၀)ပြည့်နှစ်အထိ လက်နက်ကိုင်ဆန့်ကျင်ခဲ့သည်။(၃) ပါတီ၏ တော်လှန်ရေးက မြန်မာနိုင်ငံ၏ အနောက်ဘက်ဒေသ (ပခုက္ကူ၊ နောက်ပိုင်းတွင် ရခိုင်နှင့် ဧရာ၀တီမြစ်၀ကျွန်းပေါ်ဒေသ) တွင် တည်ထားပြီး၊ သူ၏ အလွန်အမင်းအာဏာရှင်ဆန်လှသော အုပ်ချုပ်မှုကြောင့် နောက်လိုက်နောက်ပါများ တဖြည်းဖြည်း လျော့နည်းလာခဲ့သည်။ (၁၉၇၀) ပြည့်နှစ်တွင် သခင်စိုးက သူ၏ ပဉ္စမမြောက်ဇနီး၊ မွေးကင်းစသားနှင့် နောက်လိုက်နောက်ပါ (၃၀)တို့နှင့်အတူ လက်နက်ချခဲ့သည်။ (၁၉၇၂)ခုနှစ်တွင် နိုင်ငံတော်သစ္စာဖောက်မှုဖြင့် စွဲချက်တင်ခံရပြီး၊ (၁၉၇၃)ခုနှစ်တွင် သေဒဏ်ပေးခံရသည်။ အယူခံ၀င်မှုများနှင့် အသနားခံမှုများအကြိမ်ကြိမ်ပယ်ချခံရသော်လည်း၊ ကြိုးစင်ပေါ် မတက်ခဲ့ရချေ။ (၁၉၈၀)ပြည့်နှစ်တွင် ယခင်က သူ၏ ရန်သူတော်ဖြစ်သည့် ဦးနုနှင့်အတူ လွတ်ငြိမ်းချမ်းသာခွင့်ရရှိပြီး၊ နိုင်ငံတော်ပင်စင်စားခဲ့ရသည်။ (၁၉၈၈)ခုနှစ် အရေးတော်ပုံတွင် သေးငယ်သည့် အခန်းကဏ္ဍတစ်ရပ်တွင်သာ ပါ၀င်ခဲ့ပြီး၊ (၁၉၈၈)ခုနှစ် စက်တင်ဘာလ စစ်အာဏာသိမ်းပြီးနောက် တည်ထောင်သည့် ပါတီများအနက် ပါတီတစ်ခု၏ နာယကဖြစ်လာခဲ့သည်။ (၁၉၈၉)ခုနှစ် မေလ (၆)ရက်နေ့တွင် ကွယ်လွန်သည်။

၃။ ရည်ရွယ်ချက်များ၊ ရရှိအောင်မြင်ခဲ့သည်များနှင့် ပင်ကိုယ်အရည်အသွေး

သခင်စိုးသည် အသက် (၃၇)နှစ်အရွယ်၊ (၁၉၄၂)ခုနှစ်မှ စကာ အစိုးရအရပ်ရပ်ကို အနှစ် (၃၀)နီးပါး မြေအောက်တော်လှန်ရေး ဆင်နွှဲခဲ့သည်။ ဒီမတိုင်ခင် အနည်းဆုံး စာအုပ်သုံးအုပ်(၄) နှင့် စာစောင်အတော်များများရေးသားခဲ့သည့်အတွက် ကွန်မြူနစ်ဆရာကြီးအဖြစ် အသိအမှတ်ပြုလက်ခံထားကြသည်။ သူ့ရဲဘော်ရဲဘက်၊ နောက်ပိုင်းတွင် ယှဥ်ပြိုင်ဘက်ဖြစ်လာသည့် သခင်သန်းထွန်းသည် သခင်စိုးအနေဖြင့် ဆိုရှယ်လစ်၀ါဒအကြောင်း စာအုပ်ရေးသားရာတွင် “ကောင်းမွန်ချောမွေ့သည့် မြန်မာစာ“ဖြင့် ရေးသားရန် ကူညီပေးခဲ့သည်။ သူက သခင်စိုးထက်စာလျှင် ပါတီကို ကောင်းမွန်စွာ စည်းရုံးနိုင်သည့် စည်းရုံးရေးမှူး၊ စီမံခန့်ခွဲမှုကောင်းသူ၊ သခင်စိုး၏ သေးငယ်သည့် အဖွဲ့ထက်စာလျှင် အစိုးရကို ပိုမိုကြီးမားစွာ ခြိမ်းခြောက်နိုင်သည့် အဖွဲ့ဖြစ်လာခဲ့သည်။(၅) သခင်စိုး ရေးသားခဲ့သည့် ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒအကြောင်း စာအုပ်မှအပ သူ့အရေးအသားများနှင့် မိန့်ခွန်းများကို နိုင်ငံခြားဘာသာသို့ ပြန်ဆိုထားခြင်း မရှိပါချေ။ ထို့ကြောင့် “သူကိုယ်တိုင်ပြောဆိုခဲ့သည်“များကို ကောက်နုတ်ပြီး၊ သူ၏ နိုင်ငံရေးအမြင်၊ ရည်မှန်းချက်များကို ပြန်လည်တည်ဆောက်ကြည့်နိုင်ခြင်းကား မဖြစ်နိုင်ပါ။

သခင်အောင်ဆန်း၊ သခင်သန်းထွန်းနှင့် အခြားသော မြန်မာ့လွတ်လပ်ရေးအတွက် တော်လှန်တိုက်ပွဲ၀င်ကြသူများကဲ့သို့ပင် သခင်စိုးသည်လည်း သူ့ကိုယ်ပိုင်နည်းနာဖြင့် „နိုင်ငံရေးသတ္တဝါ“ ဖြစ်ခဲ့သည်။ သူ အကျဥ်းထောင်မှ လွတ်မြောက်ပြီးနောက်၊ အင်တာဗျူးတစ်ခုတွင် သူ့ကိုယ်သူ ,,ကျွမ်းကျင်တော်လှန်ရေးသမား“ ဟု ခေါ်ဆိုခဲ့သည်။ သူ့နောက်လိုက်နောက်ပါများအား သူ့အယူအဆသီအိုရီများ ရှင်းပြခြင်းဖြင့် သူ့ကိုယ်သူ ,,မြန်မာပြည်၏ ကားလ်မက်စ်“ ဟု မှတ်ယူထားသည်။ သူစာအုပ်ထဲတွင် ကားလ်မက်စ်ကို ကောက်နုတ်ကာ ,,ဤအလုပ်အတွက် ကျွန်ုပ်၏ ကိုယ်စိတ်နှစ်ဖြာ ကျန်းမာခြင်း၊ မိသားစုဘဝနှင့် အရာအားလုံးကို ပေးဆပ်ထားပါသည်။“ (စိုး၊ သခင်။ ၁၉၃၈၊ ၅၄) ဟု ရေးသားထားသည်။ စာအုပ်ရေးသားနေစဥ် သူ့ဘ၀ကို သူ့ဆရာ၏ ဘ၀နှင့် နှိုင်းယှဥ်ခဲ့ဟန်တူသည်။ နောက်ပိုင်းတွင် သူ့ကိုယ်သူ လီနင်နှင့် နှိုင်းယှဥ်ချင်လာဟန်တူသည်။ သူ့ ကိုယ်တိုင်ရေးအတ္ထုပ္ပတ္တိတွင် အချို့သော သူ့ဘဝဖြစ်စဥ်များကို ကားလ်မက်စ်ရေးသားသည့် အရင်းကျမ်း ,,Das Kapital“ ထဲမှ ရှည်ရှည်လျားလျားကောက်နုတ်ချက်များဖြင့် မှတ်ချက်ပြုထားသည်။ ထို့ပြင် သူမွေးဖွားစဥ်က သမိုင်းတွင် ကြီးကျယ်သည့် ပုဂ္ဂိုလ်တစ်ဦးဖြစ်လာမည်ကို ပြသည့် နိမိတ်ထူးတစ်ရပ် ရှိခဲ့ကြောင်း သခင်စိုးက ရေးသားခဲ့သည်။ (Taylor 2008: 11) တော်လှန်ရေးကာလအတွင်း အပေးအယူပြု ညှိနှိုင်းခြင်းများမရှိခဲ့ဘဲ၊ သူ့နောက်လိုက်နောက်ပါများ၏ လေးစားမှုကို ဆုံးရှုံးခဲ့ရသည်။ အကြောင်းမှာ သူကိုယ်တိုင် ချမှတ်ခဲ့သည် တင်းကြပ်လှသည့် ပါတီစည်းမျဥ်းများကို လိုက်နာနိုင်ခဲ့ခြင်းမရှိသောကြောင့် ဖြစ်သည်။ ,,တော်လှန်ပုန်ကန်ခြင်းအတတ်“တွင် လက်နက်ကိုင်တော်လှန်ရေးတစ်ရပ်ကို မရှိမဖြစ်လိုအပ်ခြင်းက ပဓာနကျသည် ဟူသည့် မာ့က်စ်ဝါဒ သင်ကြားပို့ချချက်ကို ယုံကြည်ကြသည့် အခြားတော်လှန်ရေးသမားများကဲ့သို့သော ကံကြမ္မာ သခင်စိုးတွင် မရှိနေခြင်းက မှတ်သားလောက်ဖွယ်ဖြစ်သည်။ သူသည် သခင်သန်းထွန်းကဲ့သို့ ,,တော်လှန်ရေးက ဝါးမျိုခံရသည်“ မဟုတ်။ သခင်သန်းထွန်းသည် တရုတ်ယဥ်ကျေးမှုတော်လှန်ရေး နိုးထလာသည့်အချိန်၊ ပါတီတွင်း အာဏာသိမ်းမှုများကို ဦးဆောင်ခဲ့ပြီးနောက်၊ (၁၉၆၈)ခုနှစ်တွင် နောက်လိုက်တစ်ဦး၏ လုပ်ကြံသတ်ဖြတ်ခြင်းကို ခံခဲ့ရသည်။ နောက်ဆုံးတွင် သခင်စိုးအနေဖြင့် မာ့က်စ်နှင့် အဲန်ဂယ်လ်တို့ထံမှ သူ့သင်ခန်းစာကို တကယ်အတည်ရသွားခဲ့ဟန်တူသည်။ ယင်းသင်ခန်းစာမှာ အရင်းရှင်ဝါဒကို ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒဖြင့် အစားထိုးပြီး လူထုက အလုံးစုံလွတ်လပ်ရေးရမည့်နေ့ကို မည်သူတစ်ဦးတစ်ယောက်ကမှ ခန့်မှန်းနိုင်ခြင်းမရှိ ဟူသည်။ (စိုး၊ သခင်။ ၁၉၃၈၊ ၈၄) သူ့အနေဖြင့် အစိုးရကို လက်နက်ချရခြင်းမှာ တော်လှန်ရေးလှုပ်ရှားမှုကျဆုံးခြင်း၊ အသက်အရွယ်ကြီးရင့်လာခြင်း၊ နောက်ဆုံးဇနီးနှင့် အသက် (၆၄)နှစ်အရွယ်မှ ရလာသည့် မွေးကင်းစသားငယ်ကို ဂရုစိုက်လိုခြင်း စသည့် စိတ်ပျက်အားငယ်ဖွယ်ရာ အကြောင်းရင်းအမျိုးမျိုးကြောင့် ဖြစ်သည်။ တရားစီရင်စဥ်ကာလအတွင်း သူ့နောက်လိုက်ငယ်သားများ ကျူးလွန်ခဲ့သည့် ရက်စက်ကြမ်းကြုတ်မှုများကို တာ၀န်ယူရန် အမျိုးမျိုး ကြိုးစားငြင်းပယ်ခဲ့ပြီး၊ နေ၀င်း ဦးဆောင်သည့် တော်လှန်ရေးကောင်စီ၏ ရည်ရွယ်ချက်များကို ထောက်ခံကြောင်း အလေးထားပြောဆိုခဲ့သည်။

သခင်စိုးတွင် အမျိုးစုံလင်သည့် ပင်ကိုအရည်အသွေးများ ရှိသည်ကား သိသာလှသည်။ (၁၉၃၀)ပြည့်နှစ်တွင် ရေးသားစပ်ဆိုသည့် ဒို့ဗမာ သီချင်းကို စိတ်အားထက်သန်ပြင်းပြစွာ သီဆိုခဲ့သည့် အဆိုရှင်အဖြစ် သူ့ကို လူသိကြသည်။ အဆိုပါ သီချင်းကို မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်သီချင်းအဖြစ် နိုင်ငံရေးတွေ့ဆုံပွဲများနှင့် အခြားပွဲအခမ်းအနားများတွင် ပရိသတ်ကို ရိုးရာဂီတသံဖြင့် ဖျော်ဖြေတင်ဆက်သည်။ ထို့အပြင် သခင်စိုးက တယောလည်းထိုးသည်။

သူ၏ အကောင်းအဆိုးဒွန်တွဲနေသည့် စရိုက်ကို ဒုတိယကမ္ဘာစစ်အတွင်း ဂျပန်တို့ကို တော်လှန်နေသည့်အချိန်အတွင်း နာမည်ကျော်သည့် ဇာတ်လမ်းတစ်ပုဒ်က ပုံဖော်နိုင်ပါသည်။ ထိုစဥ်အချိန်က ဧရာ၀တီမြစ်၀ကျွန်းပေါ်ဒေသရှိ တော်လှန်ရေးဌာနချုပ်များပေါ်သို့ လေထီးခုန်ချမည့် သူ့ရဲမေများအတွက် နိုင်လွန်ပိတ်နှင့် နှုတ်ခမ်းနီများ မှာယူခဲ့သည်။ ယင်းအပြုအမူမှာ သူ့ရဲမေများအပေါ် ကြင်နာသနားတတ်သည့် အပြုအမူအဖြစ် မှတ်ယူနိုင်သည် (မောင်မောင်၊ ဒေါက်တာ။ ၁၉၅၉၊ ၆၅) သို့သော် တော်လှန်ရေးတပ်များကို အမိန့်ပေးသည့် နေ၀င်းက သခင်စိုးအား စစ်ကို ကစားခဲ့မှုအတွက် အပြစ်ဖော်ကြိမ်းမောင်းခဲ့သည်။

၄။ ချင့်ချိန်ဆုံးဖြတ်ကြည့်ခြင်း

သခင်စိုးသည် လွှမ်းမိုးမှုရှိသည့် နိုင်ငံရေးရာထူးမျိုး မရဖူးခဲ့ချေ။ သို့သော်ငြားလည်း မြန်မာနိုင်ငံ၏ ခေတ်သစ်သမိုင်းကြောင်းတွင်မူ ကြီးမားသည့် သက်ရောက်မှုရှိခဲ့သည်။ ဒုတိယကမ္ဘာစစ်အတွင်း လွတ်လပ်ရေးကြိုးပမ်းရာတွင် သူ့ကဏ္ဍမှာ အတိမ်းအစောင်းမခံဖြစ်လှသည်။ နိုင်ငံတွင်း ကျူးကျော်လာသူ ဂျပန်များနှင့် သခင်အုပ်စုတို့၏ တရားဝင်ပူးပေါင်းဆောင်ရွက်မှုနှင့် နိုင်ငံကို ပြန်လည်သိမ်းယူရန် ကြိုးပမ်းမှုများအတွက် နိုင်ငံတွင်းမှ ထောက်ခံမှုလိုအပ်သည့် ဗြိတိသျှတို့အကြား နူးညံ့သိမ်မွေ့လှသည့် မျှခြေကို ဖန်တီးနိုင်ခြင်းဖြစ်သည်။ ထို့အပြင် သခင်စိုးသည် စစ်အတွင်း မြန်မာပြည်တွင် ,,ဖက်ဆစ်ဆန့်ကျင်ရေး“ လှုပ်ရှားမှုအတွက် ရှင်းလင်းပြတ်သားသည် တစ်ဦးတည်းသော နာမည်ကျော်ကြားသည့် သခင် တစ်ဦးဖြစ်သည်။ ထို့ကြောင့်ပင် (၁၉၄၆)ခုနှစ် သြဂုတ်လတွင် ကြေညာထုတ်ပြန်သည့် ဖဆပလအဖွဲ့ချုပ်ကြီး၏ ပထမဆုံး ကြေညာချက်တွင် လူအများယုံကြည်စိတ်ချမှုကို စွမ်းဆောင်နိုင်ခဲ့ပြီး၊ ,,ဖက်ဆစ်ဂျပန်များကို နှင်ထုတ်ရေး“ ခေါင်းစဥ်ပါ တင်နိုင်ခဲ့သည်။ အနာဂတ်နိုင်ငံတော် ဖွဲ့စည်းပုံအခြေခံဥပဒေမူကြမ်းများ ပါ၀င်နေသည့်၊ နိုင်ငံအဝှမ်း ဖြန့်ချိခဲ့သည့် ကြေညာစာတမ်းကို ရေးသားရာတွင်လည်း သခင်စိုးက ထဲထဲ၀င်၀င် ပါ၀င်ခဲ့ကြောင်း ယုံကြည်စိတ်ချစွာ သုံးသပ်နိုင်ပါသည်။

ဆယ်စုနှစ်ပေါင်းများစွာ နိုင်ငံ၏ သမိုင်းကို လွှမ်းမိုးခဲ့သည့် ဆိုရှယ်လစ်နှင့် ကွန်မြူနစ်စနစ်တို့ကို မြန်မာ့နည်း၊ မြန်မာ့ဟန် နားလည်မှုကို ပုံဖော်ရာတွင် သခင်စိုး၏ သြဇာကား အရေးပါလှပါသည်။ ရောဘတ်တေလာ မှတ်သားထားသည်မှာ။ ။

ဆိုရှယ်လစ်စနစ်ပေါ်ထွက်လာပြီး ဆယ်နှစ်အကြာ၊ (၁၉၄၈)ခုနှစ် ဇန်န၀ါရီလ (၄)ရက်နေ့ အာရုဏ်တက်ချိန်တွင် မြန်မာနိုင်ငံ လွတ်လပ်ရေးရခဲ့သည်။ ထိုစဥ်အချိန်က နိုင်ငံတွင်းရှိ အပြောကောင်း၊ အဟောကောင်းနိုင်ငံရေးမှန်သမျှ၊ မျိုးချစ်မှန်သမျှကား ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒီ၊ မာ့က်စ်ဝါဒီ သို့မဟုတ် ကွန်မြူနစ်ဖြစ်နေတတ်ပါသည်။ (တေလာ၊ ၂၀၀၈၊ ၆)

သခင်စိုး၏ လက်ရာကား ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ၀င်များ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒကို နားလည်နိုင်စေရန်၊ မာ့က်စ်ဝါဒသုံးစကားများကို ဗုဒ္ဓအတွေးအခေါ်နှင့် ချိတ်ဆက်ကာ ရှင်းပြနိုင်ခဲ့ရုံတင် မကပါ။ သူ့အနေဖြင့် ထွက်ပြေးပုန်းလျှိုနေရစဥ် (၁၉၆၀)နှင့် (၁၉၇၀)ပြည့်လွန်နှစ်များတွင်ပင် သူ့စာအုပ်ကို အဘယ်ကြောင့် ရိုက်နှိပ်ထုတ်၀ေနိုင်နေရဆဲဖြစ်သနည်းဆိုသည်ကိုပါ ရှင်းပြနိုင်ပါသည်။ သခင်စိုး၏ တပည့်တစ်ဦးဖြစ်သည့် ချစ်လှိုင်က အခြားကျောင်းသားတစ်ဦးနှင့်အတူပေါင်းကာ သခင်စိုး၏ ချဥ်းကပ်နည်းကို ယူပြီး ,,လူနှင့် သူ့ပတ်၀န်းကျင်အကြားအပြန်အလှန်ဆက်နွှယ်မှု“ဆိုသည့် ဗမာ့ဆိုရှယ်လစ်လမ်းစဥ်ပါတီ၏ အတွေးအခေါ်ကို ရေးဆွဲခဲ့သည်။(၆) အချို့က သခင်စိုး၏ သြဇာမှာ ပါတီအုပ်ချုပ်မှုကို ကျော်လွန်ကာ ခြေဆန့်ခဲ့သည်ဟု စောဒကတက်နိုင်ပါသည်။ ချစ်လှိုင်၏ တပည့်တစ်ဦးမှာ စစ်တက္ကသိုလ်ရှိ သန်းရွှေ ဖြစ်သည်။ ဖဆပလအဖွဲ့ချုပ်ကြီးကို တည်ထောင်ရာတွင် ပါ၀င်သည့် ဦးဆောင်အဖွဲ့၀င်ဖြစ်သည့် စစ်တပ်အနေဖြင့် လက်သင့်ခံနိုင်မည့် ဒီမိုကရေစီစနစ်မျိုးထံသို့ မြန်မာ့နိုင်ငံရေးကို ဦးတည်မောင်းနှင်ရာတွင် အခရာကျသည့် ပုဂ္ဂိုလ်ပင် ဖြစ်သည်။ သန်းရွှေက သူ့ဆရာ ချစ်လှိုင်ကို မမေ့ခဲ့ပါချေ။ ချစ်လှိုင် မျက်စိကွယ်သွားသောအခါ သူ့ကျန်းမာရေးကို ကြည့်ရှုစောင့်ရှောက်ခဲ့သည်။

သခင်စိုး၏ နောက်ဆုံးနိုင်ငံရေးလှုပ်ရှားမှုမှာ (၁၉၈၈)ခုနှစ်၊ စက်တင်ဘာလတွင် စည်းလုံးညီညွတ်ရေးနှင့် တိုးတက်ရေးပါတီ၏ ရာထူးနေရာကို ရယူခဲ့ခြင်းဖြစ်သည်။ ယင်းပါတီမှာ (၁၉၉၀)ပြည့်လွန်နှစ် ရွေးကောက်ပွဲတွင် (၃၆၅၆)မဲသာ ရခဲ့သည်။ သခင်စိုး၏ နောက်ဆုံးနိုင်ငံရေးလှုပ်ရှားမှုတွင် ဒေါ်အောင်ဆန်းစုကြည်ထံ သူလုပ်ခဲ့သည့် အမှားမျိုး ထပ်မကျူးလွန်မိစေရန်နှင့် စစ်တပ်နှင့် ပူးတွဲအလုပ်လုပ်ရန် အသိသတိပေးစာတစ်စောင်ကို (၁၉၈၉)ခုနှစ်တွင် ရေးသားခဲ့ခြင်းလည်း ပါ၀င်သည်။ (တေလာ။ ၂၀၀၈၊ ၁၁)

၅။ ကျမ်းကိုးစာရင်းများ

မှတ်ချက်။ ။ ဤစာ၏ အဓိက ကျမ်းကိုးသည် (၁၉၈၉) ခုနှစ်တွင် ဂျာမန်ဘာသာစကားဖြင့် ထုတ်၀ေသည့် ကလောက်စ် ဖလိုက်ရှ်မန်း (Klaus Fleischmann) ၏ စာအုပ်ဖြစ်ပါသည်။ စာအုပ်၏ အကိုးအကားများကို စာထဲတွင် မဖော်ပြထားပါ။ ဖလိုက်ရှ်မန်းက (၁၉၈၀)ပြည့်နှစ်၊ သခင်စိုး ထောင်ကလွတ်လာချိန်တွင် အင်တာဗျူးခဲ့သည်။ သခင်စိုးအကြောင်း ပိုမိုသိရှိနိုင်ရန်နှင့် သူ့အမွေအနှစ်ကို ဆေးရောင်စုံခြယ်သနိုင်ရန်၊ မြန်မာလိုထပ်မံရရှိနိုင်သေးသည့် ကျမ်းကိုးများ ရှိနေဦးမည်ဟု ခန့်မှန်းရပါသည်။

ချစ်လှိုင်၊ ၂၀၀၈။ မြန်မာ့ဆိုရှယ်လစ်လမ်းစဥ်ပါတီတွင် ကျွန်ုပ်၏ ပါ၀င်ပတ်သက်မှုအကြောင်း တစေ့တစောင်း။ ဟန်းစ်ဘန့်စ်ဆော်လ်နား (Hans-Bernd Zöllner) တည်းဖြတ် ၂၀၀၈ ခုနှစ်။ သခင်စိုး၊ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်၀ါဒနှင့် ချစ်လှိုင် အမှတ်တရများ။ မြန်မာစာပေစီမံကိန်း၊ အတွဲ (၁၀)၊ ပါ့ဆောင်းမြို့ (Passau)၊ Lehrstuhl für Südostasienkunde: 114-162. (http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs11/mlp10.10-op.pdf).

ဖလိုက်ရှ်မန်း၊ ကလောက်စ် ၁၉၈၉ (Fleischmann, Klaus) ဗမာပြည်ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ၊ အစကနဦးမှ လက်ရှိအချိန်ထိ ဟမ်းဘွတ်မြို့ (Hamburg)၊ အာရှအင်စတီကျု။

ဖလိုက်ရှ်မန်း၊ ကလောက်စ် ၁၉၈၉ (Fleischmann, Klaus) မြန်မာပြည်ရှိ ကွန်မြူနစ်ဝါဒအကြောင်း စာရွက်စာတမ်းများ၊ ၁၉၄၅ ခုနှစ်မှ ၁၉၇၇ ခုနှစ်အထိ။ ဟမ်းဘွတ်မြို့ (Hamburg)၊ အာရှအင်စတီကျု။

လင့်ထ်နာ၊ ဘာတီးလ် ၁၉၉၀။ ဗမာပြည်ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ၏ နေထွက်ချိန်နှင့် နေ၀င်ချိန် အီသီကာ၊ နယူးယောက်။ အရှေ့တောင်အာရှအစီအစဥ်၊ ကော်နဲလ်တက္ကသိုလ်

စိုး၊ သခင် ၁၉၃၈။ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒ ဟန်းစ်ဘန့်စ်ဆော်လ်နား (Hans-Bernd Zöllner) (ထုတ်၀ေ) ၂၀၀၈၊ သခင်စိုး၊ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်၀ါဒနှင့် ချစ်လှိုင် အမှတ်တရများ။ မြန်မာစာပေစီမံကိန်း၊ အတွဲ (၁၀)၊ ပါ့ဆောင်းမြို့ (Passau)၊ Lehrstuhl für Südostasienkunde: 17-106 (http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs11/mlp10.10-op.pdf).

တေလာ၊ ရောဘတ် ၂၀၀၈။ မိတ်ဆက် ။ ဟန်းစ်ဘန့်စ်ဆော်လ်နား (Hans-Bernd Zöllner) (တည်းဖြတ်) ၂၀၀၈၊ သခင်စိုး၊ ဆိုရှယ်လစ်၀ါဒနှင့် ချစ်လှိုင် အမှတ်တရများ။ မြန်မာစာပေစီမံကိန်း၊ အတွဲ (၁၀)၊ ပါ့ဆောင်းမြို့ (Passau)၊ Lehrstuhl für Südostasienkunde: 5-13 (http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs11/mlp10.10-op.pdf).

Who’s Who in Burma 1961 ရန်ကုန်၊ ပြည်သူ့စာပေရေးရာကော်မတီ

(၁) Who’s Who in Burma, 1961 (ပြည်သူ့စာပေရေးရာကော်မတီ)။ စာ-၁၅၆။ ၀ီကီပိဒီယက သူ့မွေးသက္ကရာဇ်ကို ၁၉၀၆ ခုဟုလည်း ပြထားသည်။

(၂) အမေရိကန်ပြည်ထောင်စုရှိ ကွန်မြူနစ်ပါတီ၏ ခေါင်းဆောင် Browderist ကို အစွဲပြုမှည့်ခေါ်ထားသည့် Browderist လမ်းစဥ်။ အယူဝါဒအရ အယူအဆမတူသူ ရန်သူများနှင့် ခေတ္တခဏပူးပေါင်းဆောင်ရွက်ပြီး ငြိမ်းချမ်းသည့် တိုးတက်မှုများ ဖြစ်စေသည့် လမ်းစဥ်။ ထိုလမ်းစဥ်ကို သခင်စိုးက ငြင်းဆိုသည်။

(၃) ဦးနုအစိုးရက သခင်စိုးကို အသေရရ၊ အရှင်ရရ ဆုတော်ငွေ တစ်ထောင်ကျပ် ထုပ်ခဲ့သည်။ ထိုစဥ်က အင်မတန်များပြားလှသည့် ငွေပမာဏဖြစ်သည်။ (Who’s Wo in Burma 1961: 156).

(၄) ဆိုရှယ်လစ်ဝါဒ (၁၉၃၈)၊ ဗမာ့တော်လှန်ရေး (၁၉၃၉)၊ အလုပ်သမားတို့ ကမ္ဘာ (၁၉၄၀)။ ပထမစာအုပ်ကို နဂါးနီစာအုပ်အသင်းက ထုတ်၀ေပြီး၊ နောက်စာအုပ်နှစ်အုပ်ကို နဂါးနီစာအုပ်အသင်း ပူးတွဲတည်ထောင်သူ ဦးထွန်းအေးက (၁၉၃၉)ခုနှစ်တွင် တည်ထောင်သည့် မြန်မာစာအုပ်တိုက်က ထုတ်၀ေသည်။ ဦးထွန်းအေးသည် သခင်စိုးနှင့် သခင်သန်းထွန်းတို့ကဲ့သို့ပင် ကွန်မြူနစ်ဝါဒကို စွဲမြဲယုံကြည်သူတစ်ဦးဖြစ်သည်။ စာအုပ်တိုက်တွင် ပါဝင်သော ဦးနု၏ ရှယ်ယာများကို အသုံးပြုရခြင်းသည် အရင်းရှင်ဆန်လွန်းသည်ဟု ထင်မြင်သဖြင့် စာအုပ်တိုက်မှ ထွက်ခဲ့သည်။

(၅) (၁၉၇၁)ခုနှစ် စီအိုင်အေ မှတ်တမ်းတွင် သူ၏ လက်နက်ကိုင်အဖွဲ့မှာ အဖွဲ့ဝင် ၂၀၀၊ ၃၀၀ ထက်မပိုကြောင်း ခန့်မှန်းပြထားသည်။ (https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/esau-52.pdf: 2)(၆) ချစ်လှိုင်။ ၂၀၀၈၊ ၁၂၄