Hans-Bernd Zöllner

Burmese version of this article

1 Introduction

Thakin Soe was one of the most influential members of the Dobama Asiayone and the AFPFL in the fight for Burma’s independence from the late 1930s until the country’s independence in 1948. Unlike Aung San and Nu, he did not attend university but worked in a company before he got involved in politics. Being very much attracted by socialist ideas, he wrote books and articles in Burmese that introduced Socialism and Communism to a wider audience. Later, he was the leader of a small communist party that started an armed rebellion against the government. His colourful life and character have been widely neglected due to the shift of public and academic interest on Burma after 1988. They, however, shed light on some core elements of Burmese politics.

2 Biographical Scetch

Soe was born in 1905[1] in Kyauktan, a village near Kyaikkami – known as Amherst in English – in today’s Mon State. From 1922 to 1937 he was employed by the Burmah Oil Company as laboratory assistant in the oil refinery in Thanlyin (Syriam) near Yangon. He was an avid reader, particularly interested in books on socialism that were pouring into Burma at that time.

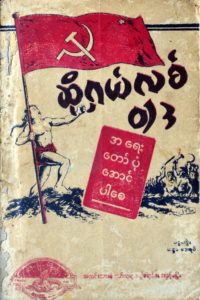

In June 1938 his book „Socialism“ (literally translated: “Socialist ideology”) was published by the Nagani („Red Dragon”) Book Club that he had co-founded together with Than Tun and Nu. Than Tun wrote the foreword. After he stopped working at the oil company, Nu supported him for some time. In 1938, he played a role in the strike of the workers on the oil fields and in Thanlyin, became a member of the Thakin movement, the Do-bama Asiayone and a member of its Central Committee, and worked as an honorary secretary at the book club, the intellectual centre of the association.

In August 1939, he was – together with Than Tun and Aung San – one of the 12 or 13 people who founded a communist party cell that later was regarded as the foundation of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB). One year later, he was – as many other Thakins – imprisoned by the British because of the agitation against the refusal of the British to promise Burma’s independence in return to the Burmese support of the war against the European Fascist powers. He was freed when the Japanese entered Burma in 1942, but unlike Aung San, Nu and Than Tun, went underground in the Irrawaddy Delta to fight the Japanese instead of initially cooperating with them. At that time, he communicated both with the British authorities in India through Thein Pe, another communist leader, who had left Burma for India. Meanwhile, most Thakins served in the Burmese government that had been set up after Japan had nominally granted independence to Burma in August 1943.

In December 1943, Soe was elected General Secretary of the Communist Party of Burma. In August 1944, the foundation of a popular front against the Japanese named Anti-Fascist Organisation (AFO), later renamed the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) comprising of the Burmese army as well as the communist party and an emerging socialist group was discussed at Thakin Soe’s headquarters and shortly afterwards was formally enacted in Rangoon. Soe was regarded as the political leader whereas Aung San was in charge of the army. He then cooperated with Ne Win who commanded an army unit in the delta as a „political advisor“ looking after the correct political attitude of the soldiers.

After the victory of the Allies in the last months of the war with assistance of the Burmese army which Aung San had led in revolt agains the Japanes in March, and celebrated in Rangoon in June 1945, Soe lost his post as General Secretary of the communist party one month later but remained a member of the Central Committee. Accusations of his weakness for women and inclination to alcohol contributed to losing his post. With the assistance of a British Communist he then travelled to India in the plane of the Royal Air Force and had talks with Indian Communists. After his return, he was strongly convinced that any cooperation with the British was wrong and an armed revolution to liberate Burma immediately from British rule had to be started.[2] After a long debate in the party over Soe’s demand to lead the party alone, he left the CPB with seven other members of the Central Committee and formed the Communist Party (Burma) called Red Flag Communist Party. The main colour of its flag was red whereas that of the “White Flag Communists” under Than Tun’s leadership was white.

The new party was declared illegal in July 1946 by the British government and went underground. Soe continued an armed struggle against the governments led by Aung San (until his assassination in July 1947), Nu (1947-1958; 1960-1962) and Ne Win (1958-1960; from 1962 on) until 1970.[3] The rebellion of his party concentrated on the western part of Burma (Pakokku and later Rakhine and parts of the Irrawaddy Delta and was characterised by a constant decrease of followers due to his extremely authoritarian style of leadership. In 1970 he surrendered together with his fifth wife, his newly born son and 30 followers. He was tried for high treason in 1972, received a death sentence in 1973. His appeals and calls for pardon were rejected, but he was not executed. He was released in 1980 in course of an amnesty and – together with Nu, his former enemy – and received a state pension afterwards. In 1988 he played a minor role in the popular uprising by becoming patron of one of the parties founded after the military coup of September 1988. He died on May 6, 1989.

3 Aims, Achievements and Personality

Soe lived an underground life fighting different governments from 1942 when he was 37 years old for almost 30 years. Before that, he wrote at least three books[4] and many pamphlets and was therefore regarded as the communist sayagyi – great teacher. His comrade and later rival Than Tun who had helped him to write his book on socialism in “good Burmese” in contrast excelled as organiser and party manager and became a much greater threat to the government than Thakin Soe’s small group.[5] Almost nothing however is known in a foreign language about his writings and speeches except the translation of his book on socialism. His visions and political goals therefore up to now cannot be directly reconstructed by quoting him „in his own voice“.

Like Aung San, Than Tun and many other Burmese revolutionaries fighting for independence, Soe was a „political animal“ in his own right. He called himself a “professional revolutionary” in an interviews after his release. He might have regarded himself as a „Burmese Karl Marx“ by explaining his theory to his fellow countryman. In his book, he quotes Marx: „To devote myself to this work, I have sacrificed my well-being, my family life and everything.“ (Soe 1938: 54) At the time of writing his book, he might have compared his life to that of his teacher. Later, he might have been inclined to compare himself with Lenin. In his autobiography, he commented on particular events happening during his life with lengthy excerpt from Marx’s Das Kapital. And he reported that at his birth a special omen had happened indicating that Soe was to become a great historic figure. (Taylor 2008: 11) During his revolutionary struggle, he did not compromise and lost the sympathies of many of his followers because he himself did not abide by the strict rules of party discipline that he had issued.

It is notable, however, that Soe did not share the fate of many other fighters who believed in the Marxist doctrine that the necessity of an armed struggle was a core element of the „science of revolution“. He was not „eaten by the revolution“ like Than Tun who was killed in 1968 by a follower after he himself had organised purges of the party in the wake of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Soe finally might have taken his lessons drawn from Marx and Engels seriously that nobody could predict the day when the complete liberation of people after the replacement of capitalism by socialism was achieved. (Soe 1938: 84). His surrender to the government was a mix of frustration about the failure of his revolutionary movement, old age and care for his last wife and his newborn son he had fathered at the age of 64. During his trial, he tried everything to reject the responsibility for atrocities committed by his followers and stressed his sympathy with the aims of the Revolutionary Council headed by Ne Win.

It seems quite clear that Soe was a complex personality. He was known to be a good singer who fervently sung the Dobama song composed in 1930 – still Myanmar’s national anthem – at political gatherings and on other occasions entertained audiences with traditional songs. Furthermore, he played the violin.

The ambivalence of his character can be illustrated by the famous story that during his resistance activities against the Japanese in World War II he ordered lipsticks and nylons for his female followers to be parachuted down to the resistance headquarters in the Irrawaddy Delta. This could be regarded as a kind gesture to his female followers (Maung Maung 1959: 65) but Ne Win who commanded the troops of the resistance unit reprimanded Soe for playing war.

4 Assessment

Takhin Soe never held an influential political post. Nevertheless he had a great impact on the course of Myanmar ’s modern history. His role in the independence struggle during World War II was crucial for creating a delicate balance between the official cooperation of the Thakins with the Japanese intruders and the British who needed local support for their attempts to recapture the country. Furthermore, Soe had been the only prominent Thakin with clear „anti-fascist“ activities during the war within Myanmar and thus provided credibility to the first declaration of the AFPFL issued in August 1946 and entitled „Drive Away the Fascist Japanese Marauders“. It can be safely assumed that Soe was heavily involved in drafting the manifesto that included the guidelines of a future constitution and was distributed around the whole country.

At least equally important is Soe’s impact on shaping the Burmese understanding of socialism and communism that dominated the country’s history for many decates. As Robert Taylor notes:

Ten years after Socialism appeared, Myanmar received its independence before dawn on 4 January 1948. By then almost every articulate politician and nationalist in the country claimed to be a socialist, Marxist, or communist. (Taylor 2008: 6)

Soe’s work had not just explained socialism in a way that could be understood by Buddhists by linking Marxist dialectics with Buddhist philosophy. This explains why the book was reprinted in Myanmar in the 1960s and 1970s even at a time when the author still lived in his hideouts. One of Soe’s students, Chit Hlaing together with another student drafted the Philosophy of the Burma Socialist Programme Party „The Correlation Between Man and His Environment“ that took up Soe’s approach,[6] One may argue that Soe’s influence even extended beyond the end of the party’s rule. One of the students of Chit Hlaing at the military academy was Than Shwe who was instrumental in directing Myanmar’s politics towards a kind of democracy acceptable to the army, the leading founding member of the AFPFL. He did not forget his teacher but cared for his health when Chit Hlaing became blind.

His last political activity after accepting the post of the Unity and Development Party in September 1988 that got just 3.656 votes in the 1990 elections was a letter to Aung San Suu Kyi written in 1989 in which he warned her not to repeat his own mistake and try to work with the army (Taylor 2008: 11).

5 Sources

Note: The main source of this text is Klaus Fleischmann’s book published in German in 1989. References to this book are not given in the text. Fleischmann interviewed Soe after his release in 1980. It can be assumed that there are many more sources available in Myanmar that can help to paint a clearer picture of Soe and his legacy.

Chit Hlaing 2008 A Short Note on My Involvement in the Burma Socialist Programme Party. Hans-Bernd Zöllner (ed.) 2008 Thakin Soe, Socialism and Chit Hlaing, Memories. Myanmar Literature Project vol. 10. Passau, Lehrstuhl für Südostasienkunde: 114-162. (http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs11/mlp10.10-op.pdf).

Fleischmann, Klaus 1989. Die kommunistische Partei Birmas. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Hamburg, Institut für Asienkunde.

Fleischmann, Klaus 1989. Documents on Communism in Burma, 1945-1977. Hamburg, Institut für Asienkunde.

Lintner, Bertil 1990. The Rise and the Fall of the Communist Party in Burma. Ithaca, N.Y : Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University

Soe (Thakin) 1938 Socialism. Hans-Bernd Zöllner (Hrsg.) 2008 Thakin Soe, Socialism and Chit Hlaing, Memories. Myanmar Literature Project vol. 10. Passau, Lehrstuhl für Südostasienkunde: 17-106 (http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs11/mlp10.10-op.pdf).

Taylor, Robert 2008. Introduction. Hans-Bernd Zöllner (ed.) 2008 Thakin Soe, Socialism and Chit Hlaing, Memories. Myanmar Literature Project vol. 10. Passau, Lehrstuhl für Südostasienkunde:: 5-13. http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs11/mlp10.10-op.pdf.

Who’s Who in Burma 1961. Rangoon: People’s Literature Committee and House.

[1] Who’s Who in Burma, 1961 (People’s Literature Commettee and House): 156. Dictionaries as well as Wikipedia give 1906 as his year of birth.

[2] Soe objected to the “Browderist line” named after the leader of the communist party of the United States who advocated a peaceful development in – temporary – cooperation with ideological enemies.

[3] Nu’s government offered a reward of 1000.Kyat – an enormous sum at that time – for his capture – „dead or alive“. (Who’s Wo in Burma 1961: 156).

[4] Socialism (1938); Resistence ion Burma (1939); Labour World (1940). The first was published by the Nagani Book Club, the two others by the Myanmar Publishing House established in 1939 by Tun Aye, a co-founder of Nagani who – being a staunch communist like Soe and Than Tun – left the publishing house because he regarded the issuing of shares supported by Nu too capitalist.

[5] The CIA in a memorandum of 1971 guessed that his armed group consisted of not more than 200-300 fighters (https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/esau-52.pdf: 2).

[6] Chit Hlaing 2008: 124.